Private Equity's SBC Opportunity

Investors, including myself, have historically lionized the ability of private equity sponsors to drive efficiency and get software businesses to 30%+ EBITDA margins. This has been the basis for underwriting private equity “put” for high-quality software businesses, at least in some part. But how durable is this rationale? And are private equity firms actually delivering on this thesis for their software investments?

Historically, the primary drivers of returns for private equity returns have been:

Value creation via margin expansion, new revenue opportunities, roll-ups, etc.

Leveraging and then de-leveraging an underleveraged business

Multiple expansion

PE firms emphasize the first lever in most of their marketing materials – Thoma Bravo claims they can drive 30+ percentage points of EBITDA expansion once they acquire a company.

But in terms of impact, multiple expansion has historically accounted for ~50% of all private equity returns. Revenue growth and margin expansion have accounted for the remainder. Margin expansion has accounted for less than 10% of the “value creation”

The impact of multiple expansion of returns is not lost on anyone, but I wanted to dig into the other lever – the ability of private equity firms to drive revenue growth/margin expansion for software companies.

Where’s the value creation?

To analyze the impact of private equity ownership on software businesses, I analyzed companies’ growth and margin structure pre- and post-PE ownership. The sample size of companies that have been public, gone private, and returned to the public markets is small, so I expanded the sample set a bit.

There are three categories1 of companies that I analyzed:

The Rounder Trippers: companies that were once public, bought out by PE firms, and then re-IPO’d. Analyzing these companies provide the cleanest view of what the impact of PE ownership has been. Companies in this group include Informatica, SolarWinds, and Instructure.

Recent PE-Backed IPOs: companies that recently came into the public markets after years of PE ownership. Companies in this group include PowerSchool, Ping Identity, JAMF, and Datto2.

Management Plans of Recent PE Buyouts: companies that were recently taken private. Analyzing these companies’ management plans as disclosed in their proxy filings provides an interesting baseline for what public companies think they can accomplish on a standalone basis. Companies in this group include Anaplan, Avalara, Coupa, Medallia, and Sailpoint3.

We used data from these companies’ public filings can be used to create an aggregated view of growth and margin profiles of software companies pre and post-buyout.

To our surprise, the margin profiles, growth rates, and combination of the two is not materially different between the two samples. Private equity ownership does not seem to have a trajectory-changing impact on the business. In some cases, such as Informatica, the actual revenue and EBIT performance under PE ownership meaningfully underperformed Management’s Plan at the time of the buyout.

So what gives?

If they cannot realize the cost savings, how has private equity made money on these deals, and how will they make them in the future?

Turns out the chart above does not tell the full story because it excludes stock-based compensation (“SBC”). We can debate ad-nauseam how SBC should be treated, but we can agree that it has an economic impact on the business because it is adding to the share count.

Over the past ten years, the SBC burden at software companies has continuously trickled up, driven by various factors (competition for talent, falling interest rates, low cost of equity). Whether this was warranted or not is a separate discussion, but it has happened.

Private Equity’s SBC Opportunity:

Private equity seems to have also identified SBC as a shadow source of margin compression in software companies. And more importantly, it’s margin compression that they can reverse (at least for a period). PE firms are using public companies’ inability to manage their dilution as an opportunity to acquire depressed software assets and meaningfully improve the economics for equity holders overnight. Since PE sponsors are the new shareholders post-buyout, they are primary benefactors.

The impact is quite clear when you compare the SBC burden at pre-PE ownership software companies with post-PE ownership software companies.

So private equity is creating value! Just not on the Non-GAAP profit metrics that software companies like us focus on.

For Thoma Bravo, which recently acquired Coupa, normalizing the company’s (rather absurd) SBC burden would reduce the annual dilution to equity holders by ~80% and increase the economic margin (EBITDA - SBC) by 22 percentage points. And in 2-3 years, Coupa could theoretically re-IPO with a reduced SBC burden. And no matter how one decides to treat SBC, the impact of normalizing SBC expenses should meaningfully benefit the equity.

One way to think about it would be that a higher % of all of the other value creation (revenue growth, margin expansion, deleveraging) accrues to the equity holders.

Informatica is a great longitudinal case study because we can overlay management’s planned SBC burden at the time of the buyout with actuals under PE ownership4.

Informatica’s management team planned to run the business with SBC representing 6% of revenues for a business growing 10-15% year-over-year. The PE sponsors ran the business at one-sixth that amount.

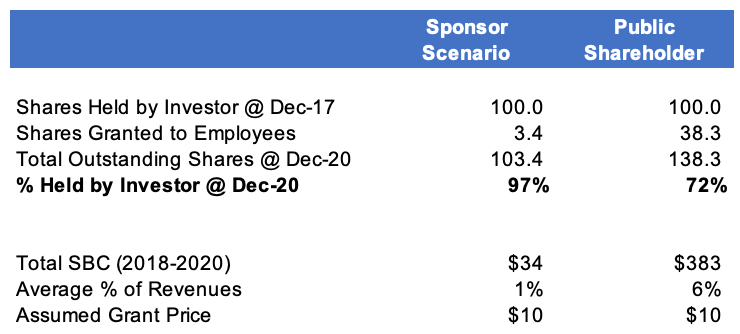

To put a finer point on how impactful the difference is: if you assume a similar grant price for both scenarios, the PE sponsor ends up owning 20-30 percentage points more of the equity than a public markets investor would have under management’s plan. Here’s a simple example that illustrates this based on Informatica’s stock-based expenses (plan and actuals)5:

You can argue that Informatica might have performed better as a public company. It might not have missed the cloud transition as much as it did, which would have justified the SBC burden, but it’s not clear that companies’ CFOs are flexing or can flex SBC as a public company.

To be clear, employees getting shares in the company is a good thing. But private equity has demonstrated that the current levels of SBC at public companies are not a requirement to run a software business.

SBC Burden on Valuation

Most sophisticated investors price this dilutive impact of SBC into the stock price in some form or another. Some burden the EBITDA/FCF with SBC costs, some just model the dilution, and some do both6. But the net impact is that the stock price is depressed by SBC, and companies with higher SBC burdens are penalized more.

Investors know that companies like Coupa et al., they are going to have to give management and employees 10-15% of the company every year in SBC. And they are okay with it as long those equity grants are attracting strong talent that can help the company grow top-line 30%+ for a long period of time. But when it does not, the return math does not work – and this is the opportunity that private equity has identified.

The common themes for the deals that private equity has done over the last 12-24 months have been:

Decelerating top-line for companies that were at one point growing 25-30%+

Some recent price dislocation likely driven by a miss on the top-line

Cash flow positive with little/no leverage

And a high SBC burden (>15% of revenues)

For software companies, decelerating the top line typically causes some degree of shareholder rotation. And the investors that are rotating into the stock typically care about per-share metrics, which means dilution matters quite a bit.

For private equity sponsors, this dynamic enables a few things:

They can acquire these software companies at a lower price because public markets are pricing in that they’ll get diluted 10-15% per year.

The intrinsic value to the sponsor is higher because they know they can remove 50-80% of the SBC/dilution overnight.

Sponsors can add 12-15 percentage points of economic margin by changing the compensation philosophy and re-IPO a company with a right-sized P&L.

Add debt (because why not).

How long will this opportunity and dynamic last for PE sponsors? Probably not long, given the current public investor focus on SBC.

But one thing is clear: public software companies’ inability to control their SBC expenses is creating headaches for public investors on both sides. On one side, public investors are getting meaningfully diluted every year. And on the other side, private equity is using this dynamic to rob public investors blind and steal these companies in the public markets.

Private equity can use their change mandate to right size SBC burden overnight. Public investors cannot, and more importantly, the management teams at public companies do not necessarily want to undergo the pain of fixing SBC, right-sizing P&Ls, and losing key people in the eyes of the public markets. Private equity gives them a safe port to land the company and use the PE mandate to fix things.

Other musings on PE…

This is not to say PE firms are out of the water on some of these recent deals even if they remove all the SBC in the world. Most of their return to date was during a period when software multiples 2-3x’d, and some of the recent deals were completed at nosebleed prices.

And there’s a whole other question of whether some companies can even return to the public markets (I think not, but that’s for a future post).

Appendix:

This is a sampling of deals that I was readily able to screen and get data for. I will proactively agree that there are likely deals missing here besides the ones I’ve decided to footnote.

This is where there’s a big sampling bias. Since we can only analyze companies that have gone public after private equity ownership, the sample is limited to software companies with (1) the growth and (2) business characteristics that public market investors will want to own. Most private equity buyouts will likely always remain private because of this.

Excluded a few companies (e.g., MeridianLink, CVent, and Dun & Bradstreet), which made them hard to analyze. MeridianLink and CVent had COVID-related noise that was hard to parse out. D&B was private for 9 months before IPO’ing.

To normalize the growth stages as much as possible, I selected the year in the management plan that had the companies growing 15-20%.

During the private equity’s ownership period, the SBC burden remains low, but as the companies gear up for the IPO, the SBC burden does increase. And in some cases, it remains quite elevated – primarily because public market investors have given companies a pass regarding SBC as long as they’re growing.

There are probably some private company accounting nuances I am missing but I can also anecdotally confirm that PE sponsors very regular include the impact of SBC savings as a source of synergy for them.

I think this is double penalizing but have not won this battle in the past

The pre-PE/post-PE table is great

This is so good.