On NVIDIA, Fading the Hype, and a Look Back at the Dot-Com Bubble

Welcome to Tidal Wave, an investment and research newsletter about software, internet, and media businesses. Quick disclaimer: this is not investment advice, and the author may hold positions in the securities discussed.

About once every two weeks, as I am doom-scrolling Twitter, a thought crosses my mind:

Why would I, not short a semiconductor stock that is trading at 23x NTM Sales and is already regarded as the bellwether name for the newly forming AI bubble? Well, precisely because it might end up being a trendy or bubble stock.

I am not the only one to have this thought. It's only been six months since ChatGPT was released, and there are already two distinct camps forming, we'll call them, Team Bubble and Team AI. For our purposes, let's loosely define a “bubble” as an environment where an asset class is priced such that no reasonable investor would expect an adequate return for the risk they're taking, and this behavior persists for a sustained period of time.

Team Bubble is proactively cautioning that a bubble is forming and points to the wild price action of stocks like C3.ai, Buzzfeed, and NVIDIA (the 800-lb gorilla). Team AI will point to the rapid adoption of ChatGPT, the demand for AI chips, and a few potentially game-changing use cases as reasons to be bullish on the trend and hold stocks like NVIDIA.

With this setup, an investor has a few options:

Option A: Go long the AI stocks (e.g., NVIDIA) because they don't think there's a bubble and believe the fundamentals will catch up to the price.

Option B: Short the asset because, well, you think there's a bubble.

Option C: Sit on the sidelines and avoid the asset class entirely either because you do not want/cannot short.

A narrative of bubbles is that unsophisticated investors (especially retail) spurred by pundits and FOMO will choose Option A. Institutional funds will choose Option B or Option C. At some point, the bubble will run out of steam, usually because of interest rates, at which point retail investors will be stuck holding the bag, and hedge funds will profit from their shorts.

However, hedge fund trading behavior during the dot-com bubble (and other periods of euphoria) presents a slightly different narrative and provides a different model for how investors, especially institutional investors, may behave in our theoretical AI bubble.

Hedge Funds During the Dot-Com Bubble

It turns out that during the Dot-Com Bubble, hedge funds chose Option D: go long the bubble asset class knowing that it is very likely a bubble1. From Hedge Funds and the Technology Bubble:

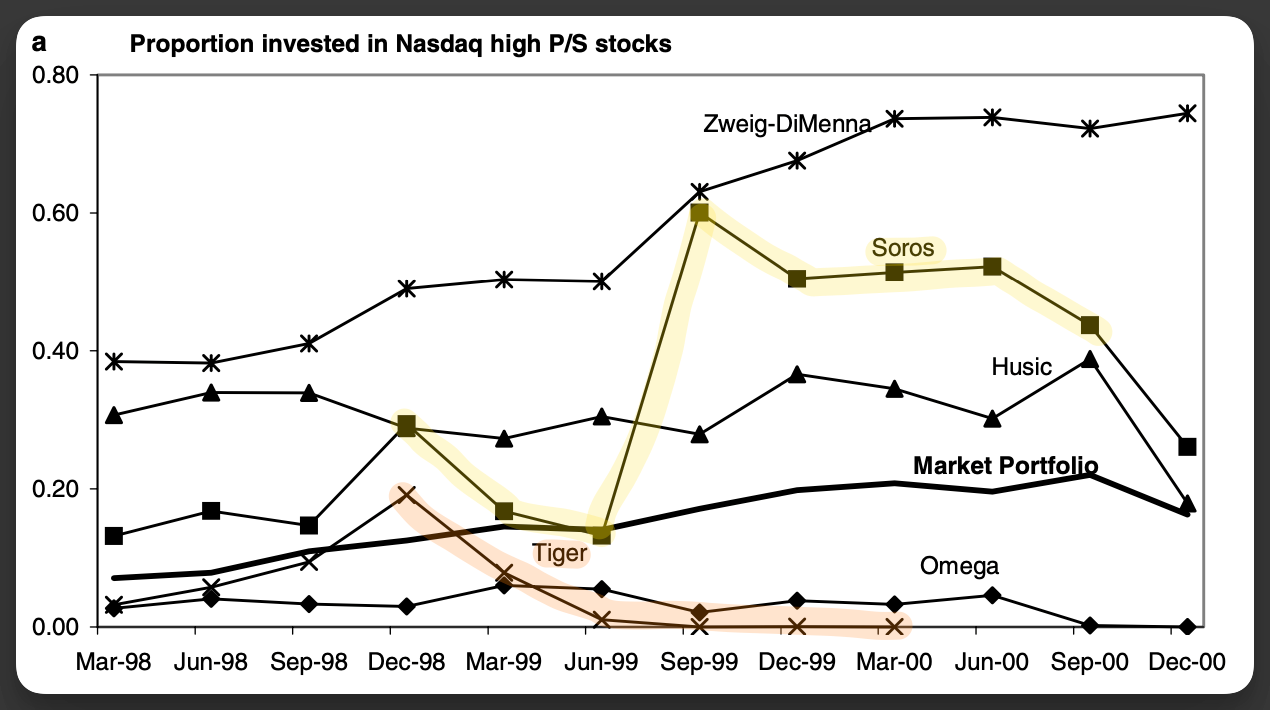

Over our sample period 1998 to 2000, hedge fund portfolios were heavily tilted toward highly priced technology stocks. The proportion of their overall stock holdings devoted to this segment was higher than the corresponding weight of technology stocks in the market portfolio. Relative to market portfolio weights, the technology exposure of hedge funds peaked in September 1999, about 6 months before the peak of the bubble. Hedge fund returns data reveal that this exposure on the long side was not offset by short positions or derivatives...

Compared to the overall market, hedge funds were overweight High P/S stocks (our proxy for bubble stocks). At the peak of the Nasdaq, 30% of the “Hedge Fund Portfolio” was invested in High P/S stocks vs. 20% for an overall market portfolio.

The data contradicts one of the tenets of efficient markets – rational investors, which hedge funds are assumed to be, should trade against mispricing.

However, during periods of sustained mispricings, institutional investors do not necessarily have Options B and C available, which limits their ability to directly attack the mispricing2. Furthermore, because rational investors cannot attack mispricing, the asset bubble persists, and prices continue to increase.

Literature on limits to arbitrage points out that various factors, such as noise trader risk3, agency problems, and synchronization risk may constrain arbitrageurs and allow mispricing to persist.

For our purposes, let's (incorrectly) say the arbitrage in the context of equity bubbles is the valuation gap between the market and the bubble stocks4. The natural way to take advantage of the arbitrage is to choose Option B and short the bubble stocks and go long the market or some other stocks you think are undervalued. But the longer the bubble persists, the riskier this strategy becomes. You run into the risk of margin calls and/or redemptions because of underperformance driven by the short positions and your longs that definitely will not be doing as well, because, you know, they're not bubble stocks.

So to go short during a bubble or these story stocks, it's not enough for you to believe the fundamentals do not support valuation, you need other market participants to agree and act in unison to drive down the price. But coordinating this behavior across investors is challenging, creating what academics refer to as synchronization risk.

Synchronization risk arises from an arbitrageur's uncertainty about when other arbitrageurs will start exploiting a common arbitrage opportunity. The arbitrage opportunity appears when prices move away from fundamental values. In a market populated by rational investors this arbitrage opportunity will be immediately explored. However, the recent literature provides evidence that small noise traders can drive prices significantly further from fundamentals...If arbitrager cannot predict investors’ preferences towards the stock, or for how long the market is going to be optimistic about the stock, the arbitrage becomes impossible. Synchronization risk, therefore, leads to market timing by arbitrageurs and delays arbitrage. (Blackburn et al)

Activist short sellers, like Muddy Waters, deal with this issue by publicly issuing well-researched and pointed reports as to why a company is overvalued or fraudulent. More recently, Kerrisdale Capital attacked C3 AI on issues related to accounting, causing the stock to drop ~25%. But the activist short playbook is usually limited to one stock. No one investor can move the whole market; unless it's Powell5. Because of this synchronization risk and the risk of being liquidated for underperformance, hedge funds are reluctant to short bubbles when they see them unless there’s a clear catalyst6.

What about Option C - just avoid the technology stocks altogether?

Some hedge funds decided to pursue this route, at least for the time, but the overall industry did not. The risk funds face is that by not owning well-performing stocks, they underperform the benchmarks the limited partners (“LPs”) set for them. LPs will tolerate the underperformance for a period, but the longer the bubble persists, the higher the risk of redemptions grows. The risk is more pronounced for mutual funds, which tend to have a more retail-oriented investor base that is inherently more flighty. Naturally, the way to avoid this risk is to have some exposure to well-performing stocks, regardless of valuation. This introduces some agency risk, which can be more pronounced during bubbles.

This dynamic was one of the reasons Julian Robertson’s Tiger Management closed shop in 2000. At its peak in 1998, Tiger had more than $20B under management. But for the final two years, Robertson shunned the overvalued tech stocks and decided to invest in value names. Unfortunately, the value stocks did not do well, and worse, technology stocks continued to outperform.

Rather than fight a bubble he viewed as absurd, Robertson decided to ignore it....

Roberston concentrated his bets on tradition value stocks such as Federal-Mogul Corporation, an auto parts supplier, and Niagara Mohawk, a power company -- the very essence of the old economy...

By the summer of 1999, Robertson's decision to ignore the tech boom was causing a crisis on Park Avenue. Tiger had lost 7.3 percent in the first half of the year; meanwhile, technology-heavy mutual funds were up a quarter or more, and day traders operating from kitchen tables were outperforming Robertson's special-forces unit. Coming on top of the losses on the yen in the fall of 1998, the latest setbacks strained investors' patience: Having withdrawn a net $3 billion from Tiger in the six months to March, Robertson's partners withdrew another $760 million at the end of the second quarter.

Unable to fight back on the withdrawals, among other factors, Robertson announced on March 30, 2000, that Tiger would be closing its doors.

To avoid a similar underperformance because of not having exposure to the well-performing stocks, funds elect to choose Option D, which is to go long the technology stocks and ride the momentum. We know that hedge funds broadly recognized that this was a bubble because many said as much (though some disagreed), and in early 1999 there was even a failed “attack” on the bubble.

Following the buildup of an overweighted position in late 1998, hedge funds subsequently reduced their exposure. This is at least somewhat consistent with the remark of Soros Fund Managements’ then-chief investment officer Stanley Druckenmiller that they were “calling the bursting of the internet bubble” in spring 1999. As it turned out, this call was too early. The bubble did not burst yet. Then, within just one quarter, hedge funds increased the weight of technology stocks from 16% to 29% in September 1999. The market portfolio weights only changed from 14% to 17%

The failed attack on the bubble was costly for Druckenmiller, who was running Soros’ Quantum fund.

At the start of 1999, Stan Druckenmiller, Quantum's supremo, had shared Roberton's conviction that tech stocks were too high; but he acted differently. Undeterred by the market's momentum, Druckenmiller had placed an unhedged outright bet against the tech bubble, picking a dozen particularly overvalued start-ups and shorting $200 million worth of them. Immediately, all of them shot up with a violence that made it impossible to escape: "They'd close one day at $100 and open at $140," Druckenmiller remembered with a shudder. Within a few weeks the position had cost Quantum $600 million. By May 1999, Druckenmiller found himself 18 percent down.

To climb out of the hole, Druckenmiller pivoted and, like others, decided to ride the wave.

Whereas Robertson had no patience for investing on the basis of momentum, Druckenmiller was fully capable of following the fundamentals in one period and surfing the trend in the next one. In May 1999, Druckenmiller allocated some of Quantum's capital to a new hire named Caron Levit, who loaded up on dot-com stocks. The skeptic who had shorted the bubble now claimed aboard the bandwagon…

When Druckenmiller returned from Sun Valley that summer, he had the zeal of the convert. He allocated more of Quantum's capital to Caron Levit and hired a second technology enthusiast named Diane Hawala…

Levit and Hakala piled into the same sorts of stock that Druckenmiller had shorted in the first part of the year. They were "in all this radioactive shit that I don't know how to spell," Druckenmiller said later. The radioactivity did wonders for Quantum's performance…

In the last months of 1999, Druckenmiller made more from surfing tech stocks than he had made from shorting sterling eight years earlier. Quantum went from down 18 percent in the first five months of the year to up 35 percent by the end of it. Druckenmiller had pulled off one of the great comebacks in the history of hedge funds, and it had nothing whatsoever to do with pushing markets to their efficient levels.

You can see the differences between Tiger and Quantum's approaches during the last two years of the dot-com bubble in their exposure to high-priced tech stocks. The flow of funds was tightly correlated to this decision.

The Fall

Even though Druckenmiller was able to masterfully guide Quantum through 1999, he too would soon follow Tiger’s fate. In February 2000, Druckenmiller pivoted out of the bubble but, a month later, would pivoted back in, leading to disastrous results.

Then on March 10 the NASDAQ turned, and many of the stocks that Quantum held fell faster even than the market. Druckenmiller himself had been a huge buyer of a firm called VeriSign, which lost almost half its value in a month…

“I knew I was dead,” Druckenmiller said later; and by the end of March Quantum had lost about one tenth of its capital.

Quantum would end up closing in April 2000, only a month after Tiger Management. At the press conference announcing the closure, Druckenmiller summarized his view:

Stanley Druckenmiller knew technology stocks were overvalued, but he didn't think the party was going to end so rapidly. "We thought it was the eighth inning, and it was the ninth," he said, explaining how the $8.2 billion Quantum Fund, which he managed for Soros Fund Management, wound up down 22 percent this year before he announced yesterday that he was calling it quits after a phenomenal record at Soros over the last 12 years. "I overplayed my hand."

March 10 would mark the peak of the dot-com bubble.

And in lock-step, hedge funds would begin to exit technology stocks (see “1” in chart below). The bear market rally in June 2000, would bring some investors back in for a short period. For institutional investors, price action seems to be the best catalyst synchronization.

Unfortunately for retailer investors, they kept buying. Both directly and indirectly through mutual funds and investment advisors, retail investors would end up increasing their exposure to technology stocks 2-3 quarters after the peak.

Who Drove and Burst the Tech Bubble?

Interestingly, independent investment advisors buy large amounts during the two quarters following the March 2000 peak and account for most of the increase in institutional holdings after the peak…

Individuals, in contrast, purchase large amounts following individual stock peaks and during the year following the market peak in March 2000…

Our results directly contrast a world where sophisticated investors consistently move against mispricing, a central building block of market efficiency. Nor does the evidence support bubble models where individuals move prices while smart money (institutions) passively stands aside…

Individual investors actively bought during both the run-up and particularly the collapse, highlighting their relatively unsophisticated behavior in the stock market.

Recent Hedge Fund Trading

Everyone following the markets over the last few years could likely draw a lot of parallels. Institutional investors were riding unprofitable technology stocks for the last ~5 years, for good reason.

Hedge funds increased their exposure in lock-step with the rise in unprofitable tech. Once the Federal Reserve began to raise rates, there was a big unwind specifically around Q4 2021 (A)7.

And similar to the dot-com bubble, retail investors kept buying for another few months.

Fading the Hype

If we overextend the lessons from the dot-com bubble and even recent trading behavior, the easy money on the momentum trade has probably already been made in NVIDIA (i.e., going long when ChatGPT came out). As evidenced by hedge fund trading behavior between 1998-2001, the incremental investor will sit on the sidelines until the direction of price action is more clear and, more importantly, the direction of the relative performance is clearer.

The risk that investors run into if they go short in the face of this type of sentiment is that at some point in the near future, NVIDIA and related stocks8 may end up being the only stocks “that work.” Funds that are underperforming but do not have exposure to these stocks may be pressured to buy, further driving up the price of the complex. Companies seeing price action in the public markets will be empowered to announce more investments in AI, further increasing investors’ expectations for underlying demand. The underlying demand for these companies may even exceed expectations!

This might sound like an endorsement to go long to ride a momentum trade and get long bubble stock, but it is absolutely not. Riding the momentum and exiting at the exact right time is a cursed strategy, which ultimately led to the fall of one of the best traders of all time, Druckenmiller.

Enthusiasm for AI and supercycle in chips may simply sputter out, in which case, it’ll be easy for investors to ride NVIDIA’s stock down to a reasonable headline valuation.

But shorting on the valuation thesis alone right now is a daunting proposition.

If you’re finding this newsletter interesting, share it with a friend, and consider subscribing if you haven’t already.

Always feel free to drop me a line at ardacapital01@gmail.com if there’s anything you’d like to share or have questions about. Again, this is not investment advice, so do your own due diligence.

Evidence of similar behavior was found in the South Sea mania and the ‘07 Real Estate bubble. Other research supports the view that institutional investors are the primary drivers of sentiment price shocks.

Well, they do, but not if they want to stay in business

Basically, anyone trades on something other than sophisticated than fundamental or technical analysis. The “sophisticated” part is open to interpretation.

To quote Matt Levine: “Webster's New World College Dictionary defines "arbitrage" as "a simultaneous purchase and sale in two separate financial markets in order to profit from a price difference existing between them," but who reads dictionaries, come on. The practical definition of "arbitrage," at least in the marketing of financial products, is "a thing we think we can make money doing, keep your fingers crossed."

This is a joke, but it’s also not. Interest rates almost universally coincide with bubbles popping, so in effect, they become quasi-synchronizing factors in the market.

You could argue that price action and, in effect, forced de-grossing, is really the main catalyst.

Anecdotally, this is consistent with the data that Coatue shared with their LPs.

Great breakdown of the dot com bubble dynamics! What’s unique about this current AI bubble is it’s forming in the context of a tight (and tightening) monetary environment, which is unusual. That said, the AI bubble is really limited to a handful of tickers, which is obviously very different than a market-wide bubble.

One parallel (or perhaps non-parallel) between 2022 and the dot-com era was how insistent everyone was that the July/August 2022 bounce was a bear market rally that would precipitate a violent move downward (a la Q4 2000). I remember seeing much of fintwit completely convinced the Nasdaq was headed below 6,000. Turns out it was a bear market rally indeed but the new lows weren't much lower than the prior lows. Now maybe we should be worried about another enormous leg downwards but unless that happens, a lot of people will have missed out buying in H2-22 because they were expecting 2022 to rhyme with 2000.

The other striking different between 2000 and 2022 is how widely divergent the NASDAQ has been from the speculative/non-profitable tech index (in 2000 I presume more of these sorts of names would have been represented in the NASDAQ), as you show in your included charts. The NASDAQ chart looks like a market that narrowly escaped another dot-com blowup; whereas in the non-profitable tech chart we're in the equivalent of summer 2003.