Generative AI, Adobe, Shutterstock, and Andy Warhol?

Welcome to Tidal Wave, an investment and research newsletter about software, internet, and media businesses. In case you missed it, here’s a link to last week’s deep dive on Databricks.

Later this week I’ll be publishing a two-part piece on Atlassian, subscribe to receive it. Quick disclaimer: this is not investment advice, and the author may hold positions in the securities discussed

Generative AI models and their ability to generate high-quality drawings, portraits, and images are testing the boundaries of U.S. Copyright Law.

Artists and owners of IP have sued the creators of models for infringing on their copyright. The most prominent cases are Andersen v. Stability AI, Midjourney, DeviantArt, and Getty Images v. Stability AI. In both cases, the owners of IP are suing the model developers for copyright infringement. More recently UMG, the music label, asked platforms like Spotify to disallow the “unauthorized” use of their songs to train the models.

On a related note, UMG has issued DMCA notices and asked the creators of AI-generated Drake and Eminem songs to take down the content from their platforms.

The original YouTube link is taken down with a message reading, “This video is no longer available due to a copyright claim by Universal Music Group” left in its place. Copies of the song are still all over YouTube, though. Ghostwriter uploads another version today; it’s still up as of this writing.

Clearly, copyright owners are not happy and they’re attacking generative AI from two angles:

Inputs: They are suing the model developers to prevent them from training their models on copyrighted IP.

Outputs: They are issuing takedown notices for AI-generated work and using the platforms (e.g., YouTube and Spotify) to police/enforce.

Copyright law and fair use, which is often used as a defense when sued for copyright infringement, in the U.S. is a bit like the Pirates Code; they are rules, but also more like guidelines and are designed to be applied on a case-by-case basis. Courts do not apply the guidelines consistently1:

As with any multi-factor test, courts have applied the fair use test inconsistently. Indeed, one of the most frequent complaints about the fair use doctrine is that it is incoherent and unpredictable. As one scholar famously put it, the fair use defense may boil down to the “right to hire a lawyer” because its unpredictability means that parties cannot actually rely on it ex ante, instead having to resort to ex post judicial adjudication before they know their rights.

The inherent uncertainty of copyright law creates FUD around using generative AI in business or commercial contexts for fear of creating something that violates the copyright. Incumbents such as Adobe and Shutterstock are starting to take advantage of the FUD to counter-positioning their offerings with the promise of compliance. Moreover, for Shutterstock, generative AI represents a more existential crisis so is using this moment to shift its business away from the quickly commoditizing stock images business towards a potentially more lucrative data business2.

A copyright case (Andy Warhol Foundation v. Goldsmith) recently heard before the Supreme Court demonstrates some of the nuances in U.S. copyright law and illustrates the problem that Adobe and Shutterstock are trying to “solve” with their generative AI products and initiatives.

Copyright 101

Before jumping into the case, it’s helpful to lay some groundwork for the discussion around copyright law and fair use. In addition to the discussion below, I recommend reading Foundation Models and Fair Use, which researchers from Stanford recently released and is a text that I heavily reference in this post.

In the United States, as soon as someone creates something, they get copyright protection for it3. The “fair use” doctrine gives others the right to use copyrighted work under certain conditions without having to get a license from the copyright owner. Courts determine something is considered “fair use” is determined based on four factors:

“the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes”

“the nature of the copyrighted work”

“the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole”

“the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work”4

The standards were meant to be intentionally flexible and this flexibility has allowed the Courts to apply copyright law on a case-by-case basis over the last 30 years. Over time, the Judicial system has introduced a number of “subfactors” to each of the factors listed above through Court Opinions. In 1994 Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc. introduced one of the most important subfactors, “transformative use”, which the court defined as something that “adds something new, with a further purpose or different character, altering the first with new expression, meaning or message”.

Since it was introduced, establishing if something is transformative has become a critical component of establishing if something is fair use or not. In “Is Transformative Work Eating the World?” researchers from BYU found that ~80% of Fair Use cases since 1994 have used the Transformative Use Doctrine in their opinions.

The researchers found that when transformative use is cited in opinions, fair use is established 50% of the time. Additionally, since many generative AI models were trained on copyrighted data, determining whether if the model outputs meet the “transformative use” bar will be important in determining whether or not they fall into “fair use”.

But the challenge has been that defining whether or not something is “transformative use” is highly contextual and critics (esp. copyright holders) have argued that it has been applied inconsistently and too broadly, effectively giving rise to unlicensed use5.

The aforementioned, Goldsmith v. Andy Warhol demonstrates how different Judges’ Courts can apply transformative use. The images and photographs in question have many parallels to the images that users of generative AI are currently making.

Goldsmith v. Andy Warhol Foundation

In 1981, photographer Lynn Goldsmith was commissioned by Newsweek to photograph an upcoming star, Prince (or The Artist Formerly Known as Prince). After being commissioned for the photographs, Goldsmith took photos of Prince at his concert and during a private studio session. Newsweek ended up using a photograph from the concert but none of the other photographs, which Goldsmith retained for future publication and licensing.

Three years later, Vanity Fair (“VF”) licensed one of the photographs from Goldsmith’s for $400 to be used in their article, “Purple Fame”, which covered Prince’s rise to stardom and hit album “Purple Rain”. The license allowed VF to commission another artist, Andy Warhol, to create a work based on Goldsmith’s photograph. Importantly the license that VF received had limitations:

Vanity Fair further agreed to run only one full-page and one quarter-page version of the illustration, which could appear only in the November 1984 issue. The license specified: “NO OTHER USAGE RIGHTS GRANTED.”

However, Warhol did not create just the one image used in the “Purple Fame” cover, he created 15 other images, now referred to as the “Prince Series”. When Warhol died, the images were passed onto the Andy Warhol Foundation (“AWF”), which over the years has sold, donated, or licensed parts of the series.

Goldsmith discovered the Series in 2016 when Conde Naste used one of the prints for their Prince tribute cover story. Goldsmith sued6 and the case went to the Southern District of New York (“SDNY”). The SDNY determined that Warhol’s Prince Series did not infringe copyright. In his ruling, the Judge determined the Prince Series constituted transformative use because:

Warhol represented Prince as “iconic” as opposed to “vulnerable” as Goldsmith originally depicted him.

the image was cropped out to the torso and neck7, and

there was no market damage because the markets were different; the licensing market for Warhol’s, because of his distinct style, is different from the licensing market for Goldsmith’s photographs.

Goldsmith appealed to the United States Court of Appeals, Second Circuit (“Court of Appeals”), which determined that the Prince Series did not meet the bar for transformative use and dismissed the lower courts’ arguments that the depiction of Prince, use of Warhol’s style and cropping of the torso as the basis of fair use:

[Regarding the first factor] the secondary work's transformative purpose and character must, at a bare minimum, comprise something more than the imposition of another artist's style on the primary work such that the secondary work remains both recognizably deriving from, and retaining the essential elements of, its source material. With this clarification, viewing the works side-by-side, we conclude that the Prince Series is not "transformative" within the meaning of the first factor…

[Regarding the second factor] While Warhol did indeed crop and flatten the Goldsmith Photograph, the end product is not merely a screenprint identifiably based on a photograph of Prince. Rather it is a screenprint readily identifiable as deriving from a specific photograph of Prince.

The Court of Appeals also made important clarifications on the market impact of the derivative work.

There currently exists a market to license photographs of musicians, such as the Goldsmith Photograph, to serve as the basis of a stylized derivative image; permitting this use would effectively destroy that broader market, as, if artists "could use such images for free, there would be little or no reason to pay for [them].

The AWF appealed to the Supreme Court, which heard the case in August 2022 and the decision is still pending. The case is heavily followed by the legal community because it has far-reaching implications for fair use but also presents an interesting lens through which to look at copyright in the context of generative AI.

Style Transfer

One of the most common prompts and uses of generative AI is “style transfer” (“Draw [Image X] in the style of [Artist Y]”8), which is analogous to how Warhol imposed his style onto the 1994 VF painting. Generative models are very capable of doing style transfer. Here’s an adapted image from a Google blog post that touts their model’s ability to accurately do style transfer.

The Warhol case is important because the ruling will likely decide on the legality of style transfer:

It is not yet clear how the Supreme Court will rule on this case, but its outcome will likely directly impact the scenario of style transfer in generative images. If the Supreme Court rules that Andy Warhol’s painting was fair use, then style transfer is more likely to be fair use9.

Taken to the extreme, in this scenario, the Court would effectively legalize the ability to superimpose an existing artist's style on existing work and monetize that work. However, styles themselves have historically not been copyrightable, which means the ruling would probably be net-negative for both owners of IP and artists, but net-positive for generative AI technology.

We find that the most common named entity type used in prompts are people’s names, including the names of artists like Greg Rutokowski, who is referenced 1.2M times. This suggests that users in this community often try to generate images in particular artist styles, which is more likely to be fair use as long as the content itself is sufficiently transformative. However, there are other queries which specifically look to generate known works of art, which would tend towards more risk of losing a fair use defense if the model complies10

In this case, style transfer would meet the “sufficiently transformative” requirement. If you are Greg Rutkowski, you are probably not happy about this outcome and usage. A quick Google Search would confirm that indeed he is not.

Copyright Liability

The second potential outcome is that the Supreme Court rules in favor of Goldsmith and determines that style transfer does not represent significant transformation. And if style transfer does not represent fair use, there is still the question of who bears the liability for the infringement. In the context of generative AI, there are four actors:

Model developers/creators e.g., OpenAI and StabilityAI

Model deployer e.g., Drayk.it, Playground AI, Jasper

End-user i.e., the person prompting

Hosting platforms i.e., YouTube, Spotify

Who bears, liability and responsibility depends on the scenario:

If, however, the court rules that this is not fair use it is less likely that style transfer will be fair use without significant transformation. There are nuances here, however. If the user provides the original image to be style-transferred, the model deployer may be less liable (since this behaves more like a photo editing software). If the model deployer only takes text and it generates copyrighted Image X in a different style, then the model deployer is more akin to Andy Warhol, rather than a photo editing software.

The first scenario is relatively straightforward. If a user of Midjourney uses the product to create work that infringes on the copyright, the user is ultimately responsible, which is the argument that Stability AI and OpenAI have made in the past.

However, in the scenario that the model itself was designed for specific style transfer, the model deployer is acting less like a photo editing software and may be liable for copyright infringement. The second example part brings to mind, Drayk.it.

Drayk.it, a music generator created by Mayk.it, recently gained steam among fans of the 6 God, who have shared their creations after making them on the site and uploading them to social media. The software allows users to select a topic of their choice, which its GPT-3 will create a song about in the style of the rap star’s own hits. Each generated song will be performed in the voice of Drake and will span one-minute in length. For those stumped or indecisive about which song theme they should choose, the site includes an option to create random topics for you by clicking on its dice icon.

Unsurprisingly, Drayk.it was taken down after a few months.

In the Drayk.it example, assuming there was some commercial aspect to the usage, there are three parties that are potentially liable:

the model deployer (Drayk.it)

the user, if they produce and distribute the Drake-stylized songs

any hosting platform that hosts content produced by Drayk.it, which can include the website host, the music platform, or eCommerce platforms that are sold MP3

Under The Digital Millennium Copyright Act (“DMCA”), online service providers are not liable if they take steps to police illegal content and importantly take down the content when they get a notice from a copyright holder. In order to mitigate legal responsibility, media and website hosting platforms implement DMCA policies that they adhere to in order to prevent lawsuits and the ire of intellectual property owners.

Copyright owners are already leveraging these platforms to take down AI-generated content.

The underlying issue and driver of the uncertainty is the fact that these generative AI models were trained mostly on data that falls under copyright protection.

The breadth of copyright protection means that most of the data that is used for training the current generation of foundation models is copyrighted material…most foundation models are trained on data obtained from webcrawls like C4 or OpenWebText. Since most online content has copyright protections attached at creation, using them for certain purposes could be considered infringement.11

If the models were trained only on licensed, publicly licensed, and/or domain content, we would not be having this conversation.

Enter Adobe and Shutterstock.

Adobe and Shutterstock Generative AI Bets

Adobe and Shutterstock, owners of large libraries of stock images, video, and audio, have recently announced Generative AI products and initiatives.

The bets are different but the core positioning is similar; as the legal owners of the licenses to these stock images, the products and data they provide their customers are legal whereas the alternatives are not. Gracefully, they do not explicitly say the last part out loud.

Just kidding, they do.

Shantanu Narayen Adobe Inc. – Chairman & CEO:

And there are a lot of questions that you can do, associated with that. I think we've been very transparent about the data that we've used. We've used Adobe Stock data. A lot of the other companies are actually using data that potentially -- they're scraping the Internet, they're accessing data that they may or may not have rights and license too.

Adobe’s bet is to make their own models trained on their stock images and openly licensed images. From their Firefly announcement:

Adobe Firefly will be made up of multiple models, tailored to serve customers with a wide array of skillsets and technical backgrounds, working across a variety of different use cases. Adobe’s first model, trained on Adobe Stock images, openly licensed content and public domain content where copyright has expired, will focus on images and text effects and is designed to generate content safe for commercial use. Adobe Stock’s hundreds of millions of professional-grade, licensed images are among the highest quality in the market and help ensure Adobe Firefly won’t generate content based on other people’s or brands’ IP. Future Adobe Firefly models will leverage a variety of assets, technology and training data from Adobe and others.

Similarly, Getty Images, after suing Stability AI, recently announced that they are working with NVIDIA to generate models on their library of stock images. In February, I wrote about the challenges Getty Images faces in this new era and why is not as well positioned as Shutterstock to make the transition to a new business model.

Shutterstock on the other hand will leverage OpenAI’s model and will license its stock images to companies developing AI models such as Meta and LG.

This content has created significant data feed and computer vision opportunities, opening up new monetization channels. In addition, we're able to commercially license this content by providing customers with the legal guarantees that they need. In 2022, we saw engagement with technology companies such as Meta, OpenAI and LG. But as we turn the corner into 2023, the size and shape of our customers has evolved to a diverse array of companies, representing technology, financial services, consultancies and other small businesses. Our most immediate use cases are generative AI, content moderation, public safety and interior design use cases.

Adobe and Shutterstock, are both marketing the same thing to their respective customers: certainty around copyright and license. In Adobe’s case, its customers remain artists/creatives whereas ShutterStock is adding a B2B channel where they license their data to the developers of generative AI models. In a hypothetical scenario where customers or developer is choosing between using Dall-E (developed by OpenAI and trained on Shutterstock’s data set) and another model (say one being sued by Getty Images), most companies will probably pick Dall-E to build their business around12.

Each company is playing to its respective strengths, Adobe’s core competency is software so they have decided to build their own models.

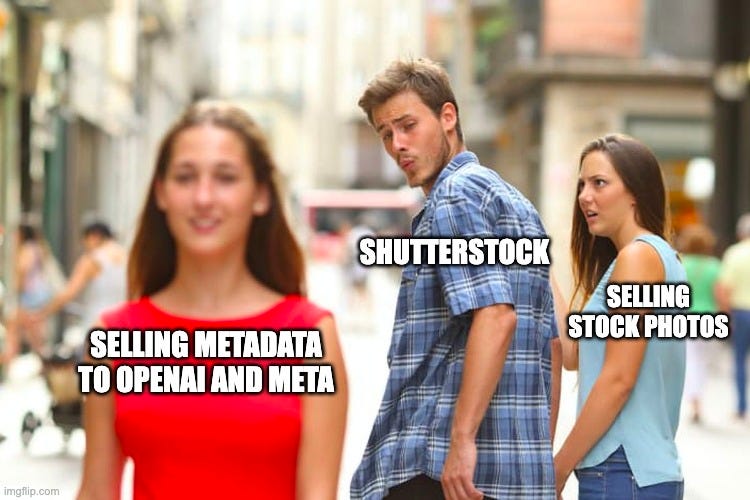

Shutterstock, which has historically built around content and its contributor network, is adding a spoke onto the flywheel to sell the metadata they are already collecting to model developers.

Shutterstock seems willing to accept the fact its content business (licensing stock images, video, audio) will be less important moving forward.

Paul J. Hennessy Shutterstock, Inc. – CEO & Director:

I mentioned the content engine [selling stock images, photos, etc]. It was the majority of our business and has been for quite some time, but I'm here to tell you that in short order in the coming years, we believe that the content side of our business will be less than half of our revenue compared to then the creative engine [self-serve editing tools and custom design] and our data engine.

The company’s “data engine” is effectively selling the metadata (tags, descriptions) on their content (e.g., photos, audio) to companies that want to use both the content and the metadata to train their models. It’s a smart strategy for a company with a large contributor network that is already uploading new content and tagging the data13.

Moreover, it would be a gross understatement to say that the threat that generative AI poses is a much larger threat to Shutterstock than Adobe. Stock images are a relatively small part of Adobe's business, they are the entirety of Shutterstock’s business. So if generative AI does disrupt the stock images market, Adobe might be okay but Shutterstock this is potentially a terminal risk they have to navigate.

The company’s focus on “data” and goal of transitioning the business away from content is a manifestation of the situation. So in some ways, ShutterStock seems to have realized that their days of selling stock images are likely numbered. In other ways, they have not.

Jarrod Yahes Shutterstock, Inc. – CFO:

Generative AI, metadata, data partnerships. Generative AI is getting really, really good, so good that it can even generate a replica of a tie from the mid-90s in purple Brooks Brothers on a CFO on a stage, incredible stuff this generative AI is capable of, fantastic. But I know 2 things that are even cooler than generative AI and cooler than metadata, and that's revenue and EBITDA.14

Additionally, Shutterstock is still pricing on a per-image basis (~$3 per image) for both stock and AI-generated images; this pricing model is unsustainable, especially for AI-generated images. Even stock image pricing is at risk in a world where the cost of generating a high-quality image is rapidly approaching zero. That being said, it’s also unwise to blow up your business model overnight, especially if you think the transition is more gradual.

For Shutterstock, an interim saving grace may be that the majority of their business involves serving eCommerce use cases. In this case, the rational thing to do would be further the uncertainty around the legality of generative AI outputs and convince the users of your platform to only rely on your creator tools:

Paul J. Hennessy Shutterstock, Inc. – CEO & Director:

…customers have peace of mind when it comes to licensing content that's created on our generative AI platform by virtue of being powered by properly, commercially licensed training data.

Also, our customers know that we're paying creators and have uniquely structured our contributor fund to compensate artists for the revenue generated by Shutterstock in connection with the licensing of generative AI content and of our training data…

All while, transitioning your business away from stock photos towards providing metadata to ML model developers. Shutterstock’s bet implicitly is that the duration of this change will give them enough runway to build a business that offsets the declines in the stock image business.

How interesting this opportunity is unclear because it’s an open question whether Shutterstock will be able to scale the data business with their current “marketplace” or if the business will effectively evolve into a professional services business. For reference, Appen is an Australian company that provides tagging services and metadata for ML use cases, the company generates ~$400M growing top-line mid-single digits and trades at ~1x revenues.

The challenge for Appen is that it is effectively a professional services business with very thin margins. However, if Shutterstock can repurpose its contributor network to tag data at scale, the business could have substantial margins and the transition story is more interesting.

Realistically, the transition will take years. The more near-term opportunity around Shutterstock will likely come from overreactions to news surrounding generative AI. As discussed above, copyright law even without generative AI is fraught with judgments and decisions that take years.

Fading the bearishness (not hype, because that’s hard) that will inevitably take over the stock is potentially an interesting trading strategy but not necessarily investing strategy.

If you’re finding this newsletter interesting, share it with a friend, and consider subscribing if you haven’t already.

Always feel free to drop me a line at ardacapital01@gmail.com if there’s anything you’d like to share or have questions about. Again, this is not investment advice, so do your own due diligence.

Is Transformative Use Eating the World? — The title is a reference to Marc Andreseen’s Why Software is Eating the World?, which raises the question, “Is the a16z content engine eating the world?”.

Yes, unfortunately, this will be the theme of the year. Companies have once again the “value” of their data.

And “soon as as” is actually quite literal. Per the Copyright Office: “Your work is under copyright protection the moment it is created and fixed in a tangible form that it is perceptible either directly or with the aid of a machine or device.”

A more nuanced discussion of each of these factors can be found in both Is Transformative Use Eating the World?

The MPAA: “It is no exaggeration to say that the meaning of “transformative use” in the lower courts has become amorphous to the point of incoherence. It fails to produce principled, consistent results or to provide any useful guidance as to what secondary uses qualify as fair use—and thus imposes no real constraint on the power of courts to authorize unlicensed uses under the guise of fair use.”

Technically AWF pre-emptively sued for summary judgment when they initially heard from Goldsmith and Goldsmith countersued. I’m sure that nuance matters to lawyers, but I was told by my editor (my wife) this portion of the post was incredibly long.

Similarly, eye-rolled when I read that too.

The example from the Stanford Paper (Foundation Models, and Fair Use).

Ibid

Ibid

Ibid

At least that’s the pitch.

The analogs are Appen and Scale AI.

This is arguably one of the most shortable quotes from a CFO I have seen.